My engagement in the history of Iran has been a short process. I basically don’t know it, but have begun trying to understand it.

Instinctively, I think of history as being fundamentally driven by material or political forces: The fight for resources or power. But Iran’s history cannot be understood, it seems, in this way and there is something I find beautiful about that. Certain pieces of Iran’s history have been driven not by material or political concerns, but by an imagination which understands events through the narratives contained within Iranian religion, namely Islam and Zoroastrianism. It reflects an experience of the world which is constantly connected to the sacred and the moral, making material and political concerns seem narrow.

There is beauty in observing historical events through the lens of religious imagination: The triumph of good over evil, the realisation of a millennia old prophecy, the approaching end of times; the narrative strength of religion provides Iranian history with an epic quality.

This is reflected in how it is expressed symbolically by the Iranian people. As these events unfold, images, myths, colours, clothing and sculpture are all brought vividly into the public sphere to reflect the imagination of the Iranian people as they associate the unfolding history with a deep well of meaning. As history unfolds, these symbols indelibly mark events with the meaning they represent.

So far, I have drawn on two sources of information; the first is the book ‘The Mantle of the Prophet’ by Roy Mottahedeh, the second is the episode of the podcast ‘Conflicted’ entitled ‘Ayatollah vs Shah’ (17th August 2022). For each small piece of Iranian history, I will reflect on their narrative beauty.

Reza Shah, The Iron Shah: A symbol of Russian and British influence.

Reza Shah ruled Iran between 1921-1945. He was a moderniser, and set about to consolidate Iran into a functioning modern nation-state. His son, Mohammed Reza Shah, took over in 1941 until the Iranian Revolution in 1979, when he was forced to flee to Egypt. Given the Islamic revolution that followed the reigns of Reza and Reza Mohammed, it is interesting to consider the symbolic significance of the image above of Reza Shah within the Iranian imagination. As quoted by Mottahedeh, Vita Sackville-West described him as:

‘In appearance… an alarming man, six foot three in height, with a sullen manner, a huge nose, grizzled hair and a brutal jowl; he looked, in fact, what he was, a Cossack trooper; but there was no denying he had a kingly presence’. (Quoted in Roy Mottahedeh’s The Mantle of the Prophet).

To grasp how this ‘Cossack trooper’ may have been understood in Iran, some very brief and partial historical context is necessary. 19th century Iranian history was heavily marked by the ‘Great Game’ between the Russian and British Empires for influence over Central Asia, primarily in Iran (then known as Persia) Afghanistan and Tibet. The legacy of this influence spilled over beyond both empires’ direct influence in Iran, as it sparked a Europeanisation of its state institutions and the beginnings of a Hobbesian modern nation state, signalling a departure from Iran’s deep history of religious, dynastic or imperial leadership. This story is demonstrated through the history of the Persian Cossack Brigade, and Reza Kahn, who used them to seize the Iranian state in 1921.

A central event in the ‘Great Game’ were the two Russo-Persian wars (1804-1813) after which Russia received territorial domination of Iran through the 1828 Treaty of Turkmanchay. Following this defeat, the ruling Qajar dynasty, were determined to build an army on the European model. To this end, in 1851 they founded the first Western-style college, staffed it with Austrian and Prussian instructors, and called it the Polytechnic College (Dar ul-funun). The college had a strong military emphasis at first, but gradually began to educate Iranian political elites in the European ideologies of modern nation-statehood, and the progress this would bring.

This ideology, and how it seeped into Iranian politics, is expressed by Mottahedeh:

Iranian elites learned that people should unite themselves in one nation-state, whose government belonged to the people and expressed their common interests. This sense of common interest, and the sacrifices it demanded, could reach the masses only through education, which had to be removed from the hands of backward priests, who had more loyalty to the church than the nation’ (Mantle of the Prophet, Mottahedeh).

Through this influence, Iranian elites were exposed to a Hobbesian conception of how a nation-state is formed. This conception can be summarised as this: Before the modern state is formed, a group of individual people must come together to recognise themselves as a single people. They can only do this by declaring that they are represented by one leader, a ‘sovereign’. Put differently, a people is only a single ‘people’ once they are represented by a single entity. As Hobbes put it: ‘For it is the Unity of the Representer, not the Unity of the Represented, that maketh the Person One’. This sovereign then has the sole right to decide what constitutes the common interest. It is the sole legitimacy of the sovereign to decide this that enables nation states to be peaceful. Without this monopoly on legitimacy, rival claims will always battle it out in a war ‘of all against all’; a civil war. If nothing else, Hobbes believed, modern states should achieve internal peace.

To consolidate power in the hands of the sovereign, the Qajar dynasty developed in 1879 the Persian Cossack Brigade, modelled on the Caucasian Cossack army of the Russian empire. In 1921 following the political and territorial break down of the Persian state, Reza Kahn led the Persian Cossack Brigade into Tehran and claimed the title of Reza, Shah of Iran. The new Shah continued with renewed intensity a programme of Western-inspired modern state building. This modernisation centred on a stable civil service, an educated entrepreneurial class and secure centralised leadership, but also relied on brutal leadership, crushing uprisings in the name of peace and stability, and earning him the nickname the ‘Iron Shah’. Hobbes condoned brutality as the legitimate exercise of the sovereign, with their sole claim to act in the ‘common interest’. In 1935, Reza Shah fired at protesters speaking out against his brutality at the tomb of Fatemeh, in Qom, the holiest Shia site in Iran, killing over 100.

This image of the Iron Shah upon his horse, like a Cossack trooper, carries this history in it. It is the European-style uniform of a military commander. Like those Europeans who wore similar, such a leader successfully claims the legitimate use of violence in a nation-state to achieve their interpretation of the ‘common interest’. It is a secular military uniform, thereby evoking the state-building ideologies of the European leaders who wore similar: centralisation, standardisation, bureaucratisation, a secular education centred on science and engineering, progress through infrastructure investment and entrepreneurialism. In sum, he symbolised western modernity, removing power from the mullahs, and moving Iran towards a more rational politics.

Iran bows to the mullahs.

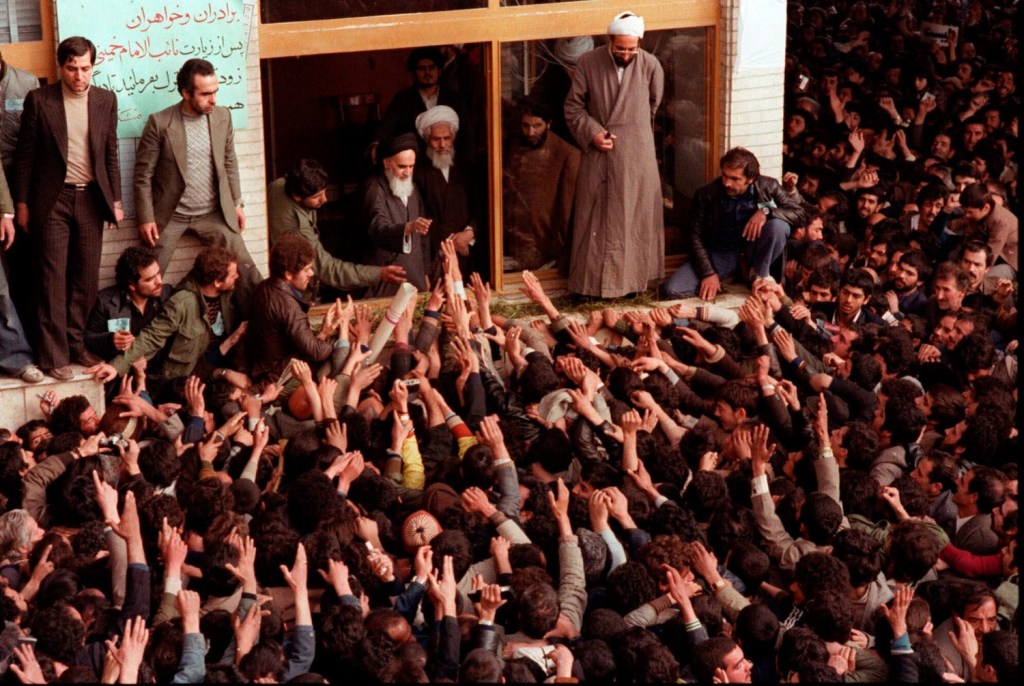

In the opening pages of his book, Mottahedeh tells the account of a mullah, Ali, born into the title of ‘Sayyed’ meaning direct descendent of Mohammed, walking through the streets of Qom in February 1979 the as the transfer of power from the regime of the Shah (Mohammed Reza Shah, the Iron Shah’s son) to the revolutionary regime of the Ayatollah was nearing completion.

‘Ali reached the crossroads, about two hundred metres from the shrine, where a police station stood, not far from two hospitals. Even though Ali had heard that Ayatollah Montazeri had sent representatives to supervise the police, he wasn’t prepared for what he saw now: a knot of policemen in their nattiest dark-blue uniforms, with military style caps, bowing slightly to a middle aged mullah, who looked at them with cautious approval as he stood outside the police station. It was then that Ali felt he could dare to believe it had really happened. How many times had he seen the police bowing in the same way to a bureaucrat, ‘engineer’ so-and-so, just getting down from Tehran in his spanking new European suit, getting out of his spanking new car for a day’s business in Qom under police escort. But the police bowing to an ordinary mullah in his turban and robe?’

People often use the image of ‘the turning of the wheel’, one kind of revolution, to describe political revolution: When the wheel turns, those who were on top, end up on the bottom. It is understandable why they are the object of such fascination, since the total reversion of the established order is the most dramatic of political stories. Yet the narrative quality of the Iranian revolution has something unique. I find the image of the secular police of the Iranian modern state bowing to a middle-aged mullah breathtaking. It is the victory of religion: Morality, spiritual belief, and myth, over the material promises of secular Western politics. Unfortunately, the government of the Islamic Republic established in 1979 has gone on to create a repressive, coercive nation state, but this does not, to me, weaken the power of that revolutionary moment.

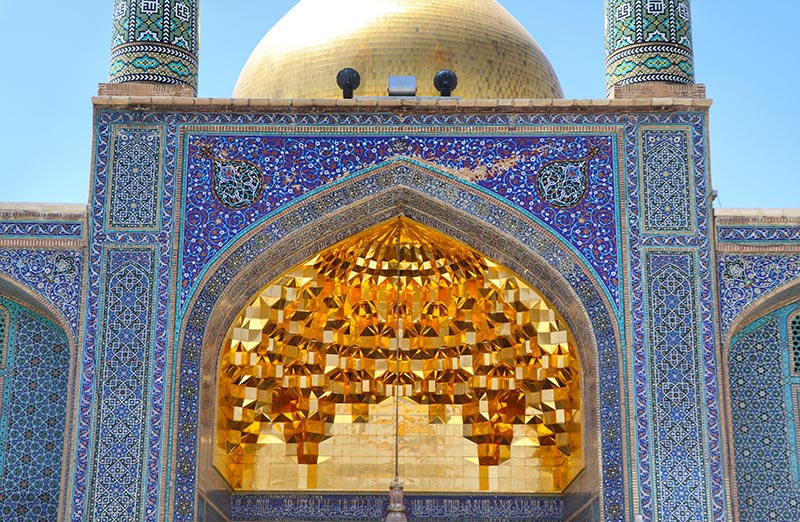

Qom

This third quote is a description of the city of Qom, in Northern Iran. Qom is the highest seat of religious learning in Iran. It holds particular significance within Shiah Islam, as it was founded during conflict in Iraq in the 7th century with Sunni groups over the rightful ruler of the Muslim empire following Mohammed, when many Shiah fled to Qom and settled there. This conflict involved the brutal death of Hosain, Mohammed’s grandchild to whom the Shia swore their allegiance, an event which is still grieved in Shiah communities across the Middle East. Hosain’s granddaughter, Fatemeh, died in Qom, and her shrine is visited on Shiah pilgrimages. Mottahedeh describes the symbolic quality of Qom within Persian Islam beautifully in the following quote:

‘Perhaps it is an accident that the Prophet’s Colour, green, is the same as the colour of vegetation, but in the painfully cultivated oasis of Qom it seems altogether appropriate. Just as Mediterranean Christian’s have for centuries marvelled that their bare hillsides can produce blood-red grapes for use as a sacrament, Iranians have for centuries loved the enclosed green gardens that their labour has won from the dry soil of their country. The ancient world knew that Iranians loved such walled-in green spaces, and the Greeks adopted the word paradeisos, borrowed from pairideeza, an ancient Persian term for an enclosed garden. The Greek New Testament adopted the same word for ‘the abode of the blessed’. How fitting that green should be the colour of the descendent of Mohammed, who, through the Koran, brought true Muslims the promise of a heavenly garden, ‘underneath which rivers flow’’ (Page 19, Mantle of the Prophet, Mottahedeh).

On the day the Iranian revolution was complete, soon after he noticed the uniformed police bowing their heads to the middle-aged mullah, Mottahedeh describes how Ali ‘rejoiced to see the two black flags of mourning for the martyrs of the revolution removed from the two minarets and a green banner tied to the top of a golden dome to signal the victory of Islam’. How beautiful for the event to have this deeply meaningful symbolic association, pulling the event from something everyday, to something sacred. The green flag marks the day with the prophet’s promise of a heavenly garden, of paradise.

The Throne of Jamshed

An important source of meaning which imbued the Iranian imagination during the revolution is the Shiah belief in the ‘Mahdi’. Shiah Muslims believe that the title of caliph (ruler of the Muslim world), was promised by Mohammed to his son-in-law, Ali. Ali, and his 11 descendants, are known by Shiah as the ‘12 imams’, the 12 rightful caliphs. Of those 12, only 2 actually ruled as caliphs. And so, the Shiah believe that, with the exception of those 2, the caliphs that ruled after Mohammed were illegitimate. Though the first 11 imams died prematurely, Shia’s believe the 12th Imam is still alive, having been given a miraculously prolonged life, but is in ‘occultation’. When he returns, the belief states, he will do so on a white horse, assisted by the prophet Isu (Jesus), vanquish evil, and unite the world under a rule of eternal peace. This is a central facet of the Shiah ideology set out by the Iranian Islamic Republic, as is the idea that Muslims are in a state of waiting for the Mahdi’s return, but that he will only do so when the conditions are right. In the meantime, it is job of Muslims to create the right conditions, the right foundations, for the Mahdi to unite the world under Islam. Khomeini capitalised on this sentiment when justifying ousting Mohammed Reza Shah during the revolution. For Khomeini could ask, how will the Mahdi return to save us, when we have empowered an oppressive, Western-educated, Anglo-American agent, as our leader?

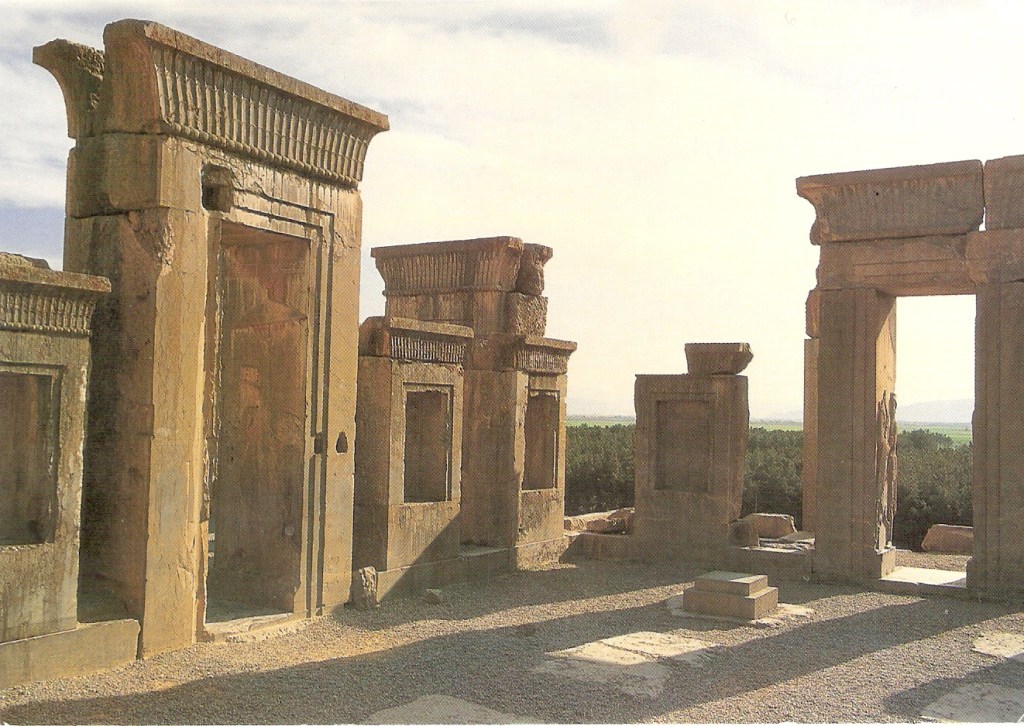

Finally, the podcast Conflicted introduced me to another source of meaning which, its host Thomas Small claims, imbued the Iranian imagination during the revolution: The Zoroastrian myth of the rise and fall of Jamshed. Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion which was dominant in Persia from as early as the 2nd millennium BC, till the Muslim conquest of Persia in the 7th century, after which it declined. Small argues the myth of Jamshed is fundamentally tied to the belief in the Mahdi because the presence of this myth within the psyche of the Iranian people allowed the belief in the Mahdi to easily take root. In a parallel sense, both sources of meaning caused the Iranian people to avidly respond to the symbology of the Ayatollah Khomeini. Small starts by by beautifully recounting the myth:

‘The possible Zoroastrian roots of the Shia belief in the Mahdi. Zoroastrianism, the Iranian religion that preceded Iran. In Zoroastrianism, God is called Ahura Mazdā, who personifies light. His arch enemy is Ahriman; he personifies darkness, deceit, sin and chaos. These two divinities are constantly fighting. Ahura Mazdā is in control, but they are in an eternal struggle. Ahura Mazdā looks down from heaven and sees human beings are greedy sinful and selfish, and withdraws the light from the earth, and without this light, everything falls into darkness, the earth becomes the realm of Ah Rahman. Now his realm is a terrible tyranny, a tyranny that to the people of earth feels endless. Yet eventually, in the midst of all this darkness and tyranny, Ahura Mazdā looks upon humankind with compassion, he finds one good man, a humble shepherd called Jamshed, and anoints him universal king, a vessel, through whom the light returns to the world. Jamshed builds a beautiful majestic throne, and he rules the world with justice, it is a time of plenty and prosperity. There is a flourishing of art, culture, and learning. But Jamshed grows proud. He begins to believe that the light, which was a gift from Ahura Mazdā, is in fact his own light. Full of hubris, he commands the people to worship him. Ahura Mazdā, and we should imagine the great god’s heart breaking, once again withdraws the light, and Ahriman returns. Ahriman anoints an evil man, Zohak, who overthrows Jamshed, and takes his place upon the great throne. This inaugurates a reign not only of tyranny, but terror, and the people begin longing for a saviour, and this saviour they call the Saoshyant, in ancient Persian. This is the Zoroastrian messiah, who, in their period of dark tyranny and terror, the Iranian people look forward to’.

This Zoroastrian myth maps very neatly onto the downfall of the Shah, and the rise of Ayatollah Khomeini. Within the Iranian imagination, he argues, the myth was being played out. In 1971, Shah Mohammed Reza organised a lavish celebration in Persepolis, celebrating 2500 years of Persian monarchy. World leaders from around the globe are invited. ‘What is Persepolis?’, Small asks rhetorically, ‘it is the throne of Jamshed, that is what Persepolis is’. Within the Iranian imagination, there, on the throne of Jamshed, the corrupt king feasts while the country toils in darkness. From the heavens, flies in Ayatollah Khomeini to save them.

The symbolic potency of these events is staggering. There is beauty in experiencing these events as deeply connected to a web of meaning, which spans thousands of years and involves divine interaction. There is beauty in the narratives and images which these webs of meaning conjure. They imbibe events with an awe-striking sense of weight and importance.

Leave a reply to charlesthomson8f63c3a369 Cancel reply